INTERVIEW WITH LIAM WILSON BY KEVIN STEWART-PANKO

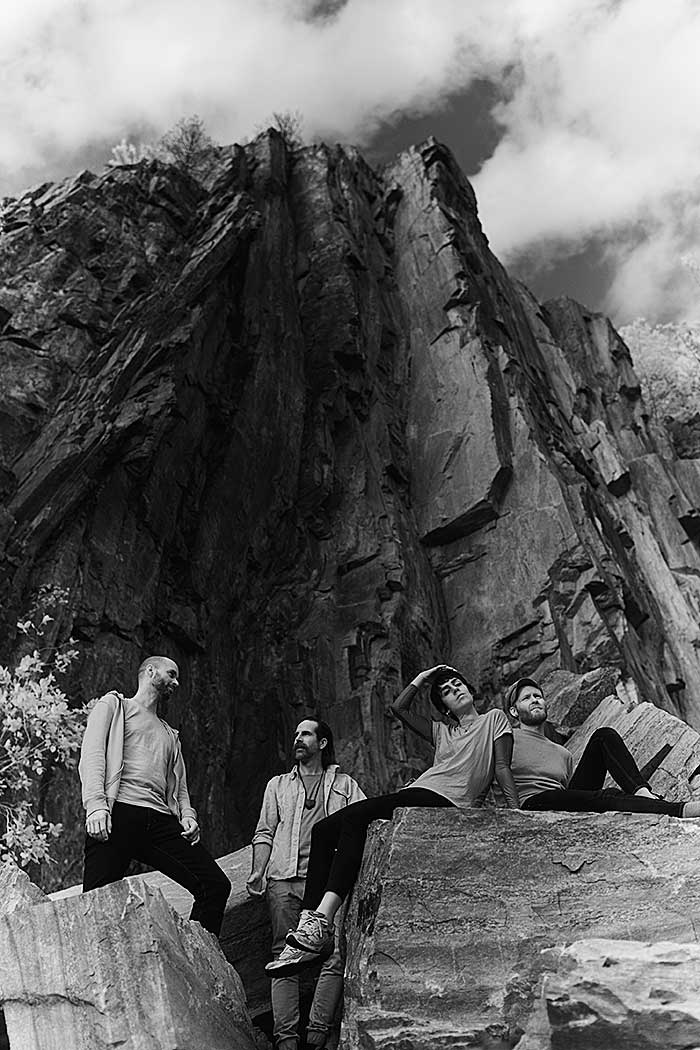

Azusa is a special and unique band. Featuring Extol drummer David Husvik, former Extol guitarist Christer Espevoll, ex-Dillinger Escape Plan bassist Liam Wilson, and Sea + Air vocalist/multi-instrumentalist Eleni Zafiriadou, there is obviously no shortage of talent and experience comprising the Azusa’s lineup. That said, backgrounds collide along the continuum from extreme metal, hardcore, and punk to atmospheric world music and indie pop, adding an intriguing bonus that has given us two albums.

2018’s Heavy Yoke and new album Loop of Yesterdays artfully blend the peculiarities, interests, and histories of its creators with the result being a broad swath of sound that never forsakes a good hook for skin searing heaviness, arthritis causing technique, ethereal atmosphere, and/or touching spirituality. Also notable is the fact that this band and their recorded output manage to exist at the high level of quality it does. With Husvik and Espevoll living in Oslo, Wilson calling Philadelphia home, and Zafiriadou splitting time between both Germany and Greece, one can imagine the bandwidth and frequent flyer miles needed to keep Azusa afloat, but the quartet makes it work.

Surmounting this unenviable logistical task is Loop of Yesterdays, which possesses cohesion amongst variety while still delivering a noticeable curb kicking forwardness. We got in touch with Wilson, the member of the band living in the closest time zone to us, to chin wag about multi-directional personal interactions, having fun transcontinentally, and how hard times and hard lives breeds hard music.

Azusa is still relatively young and you have the unique circumstance of members spread all over the place. What can you tell us about the band’s history?

Going all the way back to the very beginnings is the safest place to start. Sometime around when Dillinger was recording Option Paralysis, I was thinking about what sort of bass tone I was going for and what I could do to do something different. I was really into Extol’s Synergy record and loved the way the bass cut on that record. So, I reached out on Facebook to who I thought was the bass player and was like, “Big fan of the record, wondering if there’s some secret sauce or a secret Norwegian pedal that I’m not aware of?” (laughs) I’m not really much of a gear nerd, but I was looking for any help. I mean, the further I got into my career, the more I realized that none of that shit even matters. Anyway, I never got the answer I was looking for. The guy I got in touch with was like, “I was only the live bass player and I’m pretty sure one of the guitarists tracked the bass for that album, but I’ll let them know you’re a fan because I think they would think that’s cool.” That was 2009-10. Fast-forward to 2014 or so and I’d forgot all about it, but got an email or Facebook message from either David or Christer saying that they had some material they’d been working on that’s not quite going to work with Extol and asked if I was interested. I was. At the very least, I was flattered and asked them to send me what they had. What they sent ripped and sounded like Synergy era stuff. They said that some of that stuff was coming from the orphan riffs of that writing cycle, stuff that didn’t quite fit, but that they still loved, but couldn’t build something around it. From there, it started pretty quickly.

“THE MUSIC’S GREAT, BUT I DIDN’T WANT TO HAVE JUST ANOTHER DUDE GROWLING OVER IT. WE’VE ALL DONE THAT.”

Why put yourself in this situation with the lineup as opposed to forming a band with dudes from down the street?

I was! I was doing the John Frum stuff, Dillinger was still going, and those were all dudes who were nearby. John Frum was all Philadelphia guys, and we practiced in my basement once a week without caring how long it took to write. Dillinger had everybody just far enough away, but close enough to keep it in balance. What turned into Azusa was us having no agenda and just wanting to keep plugging away at something. As long as there was no timeline, I was like, “Let’s do it.” There was a lot of back forth, sending files, videos, a little bit of demoing and then we hit the point where we almost had a record but didn’t have a vocalist. That was a whole other conversation. Usually, you get 3/4ths of a band together and sweat that last member, and that’s what we did. We reached out to some people and nothing seemed to click. Around that time I filled in for Myrkur on their US tour after their bass player did one show and got the tragic news that his mom died, so he had to fly home. A good friend of mine was their tour manager, they were on Relapse, and there was a connection between me and the Relapse people and it was like, “You’re the bass player we think can learn this faster than anybody we know. They’re actually in Philly tonight, go meet them at their hotel and talk and see if you want to do it.” I ended up on that tour, and that was the first time I’ve been in a situation with a female fronted band. I really dug it! The energy was great. It was nice not just having a bunch of dudes in the band, and that to me was an exciting dynamic and I wanted something fresh. That tour was over in about three weeks, and I missed that vibe. I came back and mentioned to David that I was open to being female fronted, if we could find someone. Everything else that was being suggested was just making it into another band, and it wasn’t very exciting. The music’s great, but I didn’t want to have just another dude growling over it. We’ve all done that. David was like, “It’s funny you say that. I’ve got someone in mind. Let me reach out and see if she’s available.” I guess he had seen Eleni’s old band, Jumbo Jet, which was kind of like a hardcore band, and she had a cool, wacky, and psychedelic vibe on stage that he always thought was cool. Fast-forward some more and she sends some demos and it was fucking cool! And there we had it. I would fly in and that was kind of funny, too, because at that point, I had never met any of them. I’m up in my head thinking they were going to think I was like Satan’s son or something, or at least not like them. But within an hour, we were kindred spirits. We’re just similar enough to make this exciting and definitely on the same page about a lot of things, but just different enough as well.

With all distance and logistics being a factor, how does the band exist operationally?

For the recordings, I would fly in, do like five or six songs, hang out for a couple of days, and then I would leave. And right before I would get there or right after I’d leave, Eleni would come in and do as many songs as she had time to do. I think over two or three trips, it worked out. Some of it would be like, Dillinger’s playing a show in Oslo, so I’d run over to David’s studio and track a song. Or I’d end up in Europe for some reason, or it’d be convenient so I’d stay for two extra days to record. So, at that time, even though we were on different sides of the planet, I was traveling so much that it actually fit in. It’s a little bit different now that I’m not traveling as much, but it still works. Really, Oslo is only six hours away. That’s not even a full workday and I’m already there. When we did the video for the new song “Monument,” I left Philly at like three in the afternoon, got there the next day at like 11AM and when I landed I already had an email in my inbox saying I could check in for my flight home. I went for less than 24 hours, shot the video, and came home. As complicated as that is, it’s doable as long as the budget is there. There’s a way to make it work.

After Dillinger, was it your plan to do Azusa more, or at least do it and have it be easier?

It was a combination of both. At the same time, I think the John Frum album [A Stirring in the Noos] was being released, so that was done, mixed, and being pushed out and promoted. Azusa was kind of the other thing. Dillinger was such a big chunk of my life that it was like, “If I had time for that one big thing, then I surely have time for two medium sized things, if not more.” (laughs) And it satisfied something else. I like technical, challenging music, and I’m kind of typecast for it, and at least as far as my ego was concerned, it was a really nice airbag to have. Creatively, I was putting as much, if not more into this with a little bit more wiggle room because it’s not as demanding on my schedule since I can work on it at home instead of driving to Jersey a couple times a week to practice.

“CREATIVELY, I WAS PUTTING AS MUCH, IF NOT MORE INTO THIS”

And a lot of this material came from the orphans of the last Extol writing sessions…

Well, it was the last of the Synergy record. I think they did two more records after that without Christer. This was Christer and David’s way of reconnecting. They’re cousins, they grew up together and started Extol together with Christer’s brother as the singer. Christer left and they did a couple more records, then [vocalist] Peter [Espevoll] couldn’t do it anymore. David and Christer ran into one another and talked about getting together and doing something with the leftover stuff that was sitting on a hard drive somewhere. When they were talking about bass players, my name came up as someone who was interested. So, they swung for the fences.

With everyone’s schedules and lives in consideration, what was the intent after the release of the first album? Were there plans to play live, etc.?

I know that David has said that he lost inspiration for Extol and for the time being he needed to put a pause on it. But he wasn’t sick of music, he just thought Extol lost its breath for awhile and he needed to catch that breath. I’m putting words in his mouth right now, but that’s the impression I got. I knew he wanted to do something and I knew he liked the idea of playing shows, which was my idea, too. There were a lot of reasons why John Frum didn’t play as many shows or go as hard as we could have after that record came out, and I felt blue balled myself a little. Some of it had to do with the Dillinger bus accident and our schedule. My plans were kind of dashed. I made it pretty clear that even if it was only 10 shows a year, I didn’t want Azusa to just be a studio project. For me, the final brushstroke is going out and playing it live, even if it falls flat on its face. For the fans, you have to give them a little bit and let them know that you’re at least active somewhere and at some point. To me, that’s important.

How much did you play live after Heavy Yoke?

So far I think we’ve done about three weeks of shows in Europe.

“THAT’S THE OVERARCHING THEME OF THIS RECORD IN GENERAL. HEAVY YOKE WAS THE IMPACT. LOOP OF YESTERDAYS IS THE AFTERMATH.”

Would you say you learned anything from those live shows that was applied to the new record?

Yeah. For one, even though we got to know each other before the tour, it was usually these weird one-way interactions. Like, I’d get to know David when I’d be in the studio tracking with him, or David and Christer a little bit when David would have time to stop by, or Christer and I would go hang out while David and Eleni were tracking something, or Eleni and I would separate ourselves because we were the ones not speaking Norwegian. Eleni even came to a Dillinger show when we played in Germany. Getting on the road was the first time that, not only were we hanging out in the same room for a significant amount of time, but it was the first time we were really together. All the bugs started to show up and people’s personalities—their senses of humor, the way everybody plays off each other. There was a bit more realness and tension, but also a lot more joy because we were out there doing it. It didn’t have the same attitude as Dillinger, which is the biggest thing I have to compare it to, which was serious and take no prisoners. We were having fun occasionally, but it was pretty serious and high stakes and we were out for blood. This was a little bit more like a victory lap. Not that we didn’t take it seriously, but it was like, “Let’s have fun!” We worked hard, wrote some sick riffs—let’s show this to people and be proud of ourselves. Heavy Yoke was written before we knew Eleni was going to be singing and before they knew I was going to be playing. When we were writing this one, we all knew each other’s strengths and weaknesses a little bit more and we got to play to them. There was also more comfort and trust, and that was the biggest thing. You just trust each other more because we had already done it, and there’s not that much to prove. I think that’s the overarching theme of this record in general. Heavy Yoke was the impact. Loop of Yesterdays is the aftermath.

Did you spend much face to face time when writing the new album, or did you go straight from being in front of your computer screens and home recording setups into the studio?

Most of it was done straight to the studio. David and Christer meet once a week—almost every Thursday for the past five years—and they go get something to eat, then go into the studio and start throwing things around. They wrote a lot of it. David is like the mastermind. He wrote a lot of the guitar, and if you need a vocal harmony, a vocal line, a melody, he’s the man. They would write stuff, send it to Eleni and I, I would woodshed it, sometimes Christer would send me a really crude playthrough to help. We would just show up in the studio, I would throw my ideas out and see what sticks. There was a lot of demoing back and forth with this record because of that trust factor. The first time around, they wanted to know that I could pull it off before I flew over there and wasted their time. They’ve heard Dillinger, but there’s a lot of studio magic that could have happened and whatever. They didn’t really know me. I could have been a drunk asshole and not have been able to pull it off (laughs). There were a lot of unknowns then, but this time around we knew we could get together and fucking do it. I think part of this record was also not being so ego driven. As a band coming out after Dillinger, after Extol, it was like, “Man, we gotta nuke these people and tear their heads off!” This time around it was more writing what we wanted to write and something that’s not so much ripping people’s ears off and blinding them as it is punching them in the gut and making them feel that their heart is melting. Going more for feeling than thought, not wanting to prove as much as wanting to say.

“IT IS PUNCHING THEM IN THE GUT AND MAKING THEM FEEL THAT THEIR HEART IS MELTING.”

Is there a story behind the title? Is it thematically running in opposition of the idea that those who don’t understand history are doomed to repeat the past, as well as the definition of insanity—doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results?

Yeah, it’s sort of like that, though it would never have passed the smell test with all of us if we all didn’t have some association with it. This time around one of the hardest things is that because we’ve gotten to know each other and because we’re trying to be as democratic as possible, things like the artwork and album title were way harder. The first time, Eleni and I were like, “Well, let’s let David and Christer do the groundwork.” It was like they built the house then we came along and painted the walls and picked out the furniture. This time everyone wanted to have their say in this four-way thing. That said, I’m pretty sure the title came up due to personal stuff because a lot of life happened for everyone, good and bad, since the last record came out. Everybody had something happen, so on a metaphysical level, what went into the lyrics or what actively and consciously went into our playing, it’s all in there. In some cases, it was an uplifting joy that got in the way, other times it was like being fucking nuked. It was a weird dichotomy and push-pull and a collision of everything that led to the title, like we can’t get caught in memories of old emotions, a loop of yesterdays.

So, there was a variety of feelings and emotions that went into the totality of the album?

I still want to make art as it mimics life because my life is just getting more complicated and the shit that I was talking about with my music when I was 20 seems like an episode of Sesame Street now. Shit is so much more real and art is so much more valuable and necessary as an outlet. I’ve never burned with more passion for it than I do now because I need it and my problems are more relevant and real. When I was 20, it might have been about how someone broke my heart after we were dating for six months. You can write an emo record about that shit and certain bands have made careers out of that (laughs). For us, it’s like shit got real—death, disease, divorce, kids, loss, and all that shit piles up. Life is suffering, and heavy life deserves heavy music.

“LIFE IS SUFFERING, AND HEAVY LIFE DESERVES HEAVY MUSIC.”

Are you planning on doing anything differently with the Loop of Yesterdays album cycle, given that you have some logistical and personal experience now?

I definitely think it’s going to be similar to what we did with Heavy Yoke. We have a booking agent, and we’re looking for stuff to do. If it’s not a support tour, it’s going to be hard to do anything. We may have 10 or 20 rabid fans in London or something, but if we can’t get 100 people out, it’s not going to be worth it, and that’s just the reality of the industry right now. Our goal is to pull every favor, relationship, and connection we have and message them. For me, it’s like hitting up every band that Dillinger ever took on tour, and now that all those bands are bigger than Dillinger, saying, “Hey, if we’ve ever had a good time together playing a show, why don’t we do it for three weeks in a row?” The goal is to get Azusa out to the point where we can go out and play shows and maybe it’s going to take three records, I don’t know. That’s the state of things for a lot of bands unless they’re 20, have no relationships and jobs they don’t give a shit about. I put so much of my life on hold to do Dillinger and I don’t regret a single beat of it, but I dropped out of art school and now after a couple years of detox from that, I’m back working in the art world and it’s super fucking cool. It may not be the best pay in the world, but I get to do some super fucking cool shit, stuff I put aside to do Dillinger. So, I’m trying to respect what fans want, but I can’t just do what everyone wants us to do when I’ve already done that for so long—sacrificed myself, my happiness, my mental health to do that. I know that’s not necessarily what people want to hear, but don’t hate the player, hate the game. If everyone was buying CDs and records and bands were getting advances to go on tour, it would happen. A lot of the reason we were able to end up solvent on the shows we did do was because the Norwegian government was just generous enough so that we could break even.